Confronting the global ecological emergency will require a mobilization far more ambitious than any actions now being considered by governments or international bodies. In response, several of the people and groups urging much more drastic action here in America have been saying that it needs to happen on the scale of the country’s mobilization for World War II 75 years ago.

One of the most prominent invocations of the World War II model was a 2016 call to arms by Bill McKibben in The New Republic. He wrote, “It’s not that global warming is like a world war. It is a world war.” In arguing for a rapid buildup of renewable-energy infrastructure in this century, McKibben focused on just one aspect of the wartime experience of the 1940s: the surge of human and industrial resources that arose and carried the war effort.

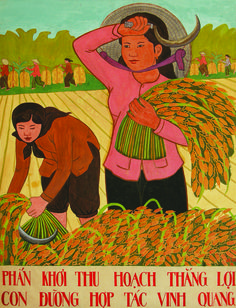

(Above: roughly translates as "Children bring in the glorious harvest")

While there is no doubt about the need to replace fossil energy, I have argued that the more important lesson to draw from World War II is that a society can, if pressed, ration its material production and consumption in order to function well on a deeply constrained flow of civilian goods while ensuring sufficiency for all.

But relying on either the production achievements or the economic planning of the wartime 1940s (or both) as a precedent for action right now would depend on having (a) a government that is willing to enact and enforce the necessary laws and (b) an owning/managing class that is willing to go along with disruption of their profitable activities and refrain from sabotaging our efforts to pull the economy back within ecological limits.

Obviously, we have nothing like those conditions in today’s America. In creating those conditions, the World War II story is no help to us because (a) the government will always respond much more forcefully to a military event like Pearl Harbor than it will to predictions of ecological breakdown decades in the future, and (b) today, there is no counterpart to the massive armaments buildup that kept corporate America profitable and happy in the 1940s. Neither business nor government will go along with the reduced production and egalitarian resource policies that are required if we are to stop crossing ecological red lines.

In seeking to create the political and economic conditions for what Fred Magdoff and Chris Williams call an “ecological revolution,” I suggest that we move on from World War II to another historical episode, one that’s also set in wartime.

Before proceeding, I apologize for staying with the war theme. I am against violence, but the system that confronts us has different ideas. As Magdoff and Williams point out, any mass movement for ecological regime change will almost certainly be met with corporate and state violence. So civilian experiences in wartime are relevant.

I argue that in the drive to create a society that’s capable of the necessary ecological mobilization, we can draw inspiration from the struggle of the Vietnamese people against the American war machine in the 1960s and 1970s.

This is not to ignore the U.S. antiwar movement, which was radical and fearless. By putting their bodies on the line at Jackson State, Kent State, Chicago, and elsewhere, antiwar activists exposed the corruption and violence at the heart of the U.S. power structure. But in the end, it was the people of Vietnam who sent the invaders packing and put an end to the slaughter.

It was not just a battlefield victory. Had the Vietnamese effort to evict the invaders relied solely on military action, it would not have succeeded. It was through their larger and broader efforts to keep their society intact and viable that the Vietnamese people prevailed in their struggle—one that today would be filed under “asymmetrical warfare” even though it involved much more than warfighting. The coming asymmetrical struggle for an ecological society will require of us a similar magnitude of effort and resolve.

Facing an existential threat from a superpower with unlimited resources, the people of Vietnam relied on their deep knowledge of their ecological context, the mobilization of human power on an epic scale, a collective resourcefulness and seeming fearlessness, careful management of scarce material resources, a willingness to work for the common good rather than personal gain or comfort, a refusal to be co-opted by either enemy government, and the will to stand up to a great power that’s capable of wreaking massive destruction.

If a population threatened with annihilation by bombs needs do all of those things, one threatened by global ecological meltdown may need to do them even more.* Some of these features of the Vietnamese approach can be seen reflected in some of America’s ecological struggles—for example in the oil-pipeline showdowns. But the wider mainstream movement remains enthralled by the prospect of shiny new technological fixes.

Interviewed in Ken Burns’ 2017 documentary The Vietnam War, a former North Vietnamese Army soldier named Bao Ninh, recalls those days:

Of course a soldier’s life is miserable. Even the American soldiers were miserable . . . But they weren’t starving. They couldn’t starve. We had to forage for food. Our army could give us only a bit of rice and salt. We were always searching for American food. They called them C-rations. A regular American soldier carried enough food for a picnic. Everything you’d want.

Shingo Shibata spent four weeks in Vietnam as Secretary General of a Japanese investigative team looking into U.S. war crimes. In a 1968 Monthly Review article titled “Vietnam Will Win,” he provided a glimpse of what life was like at the height of the war:

Bomb craters in the fields are soon filled up and the crops are planted. Thanks to [such] "deep plow[ing]," these crops grow faster than others. Bigger craters are used as fishponds, with aquatic plants on the surface and vegetables and fruit trees planted around . . . Even while American planes are flying overhead, the Vietnamese often continue working in the fields. Only when the planes turn toward them to attack do the farmers dive into their foxholes and come to the ready. Even buffaloes have learned to lie down or go into trenches made especially for cattle. . .

. . . before the revolution for independence in 1945, as a result of Japanese imperialism some two million people, that is, one out of seven, starved to death in North Vietnam alone. Compared with those days, even with houses and buildings destroyed by the bombing, the standard of living of the people is much higher now, and every person can have adequate rice and meat. So the food problem has been solved. Thanks to the socialist system, wartime evils common to capitalist economy, such as cornering, withholding, speculation, and inflation, cannot flourish. Even under wartime conditions people carry on planned, rational, industrial production. Even construction of shelters and new houses, sanitation works, and culture and education are all going on along with fighting and production, all undertaken purposefully and collectively under the cooperative system.

The Vietnamese people couldn’t and didn’t try to beat the Americans at their own game by developing overwhelming firepower. And we’re not going to head off ecological breakdown by relying on the same distorted economic and political structures that are already hollowing out the ecosphere while producing a surplus of human misery.

If we are to aim instead for “system change, not climate change,” it will be time to file the World War II experience away for future reference and learn first from the experience of the Vietnamese people—while at the same time supporting a host of present-day ecological struggles worldwide, from Standing Rock to India’s coal country, to communities all over South America.

Stan Cox (@CoxStan) is on the editorial board of Green Social Thought. He is author of ‘Any Way You Slice It: The Past, Present, and Future of Rationing’ and three other books.

Note

* Their determination and resourcefulness has nothing to do with the doctrine of “resilience” that is still very popular in the international development establishment. Under the doctrine, communities already saddled with scarcity are expected to exhibit resilience by, for example, riding out any environmental catastrophe and restoring their previous low quality of life without rocking the economic boat. Meanwhile, affluent populations are supposed to express their resilience by maintaining GDP growth, whatever shocks may come. The resilience doctrine is a trap.