Robert’s experience shows the ubiquitous presence of conditions that stretch from condemning Black (and brown) neighborhoods to rot, over utilizing the criminal so-called “justice” system to keep Black (and brown) people “in their place,” all the while feeding the prison industrial complex, to the total disregard of mostly Black (and brown) prisoners’ lives. The underlying cause here is more than just “racism” that could be “educated away,” “fired and replaced” or “de-funded.”

What I describe below, is the reflection and expression of an economic system—and its “players”—that systematically colonizes Black and brown people here and around the world, designed and destined to continue doing so unless challenged and overturned.

In this context, Robert experience shows the crucial and powerful role state attorneys and parole officers play in the judicial process, including determining who gets charged and locked up, as well as a parolee’s success or failure. It also reveals how being black to this day poses a severe disadvantage from start to end, since state prisons are almost exclusively located in struggling white, rural areas where prejudice and racial bias prevail.

Institutional decisions that determine a prisoner’s daily life as well as his ultimate fate — disciplinary measures, access to programs, prison jobs and leisure activities, treatment outcomes, medical and psychiatric care, the granting of parole — are often guided by attitudes that are at best ignorant and culturally incompetent, and at worst openly arbitrary and racist. Furthermore, Robert’s exposure to drug treatments in prison shows the ineffectiveness of boot-camp style programs whose focus is obedience and subordination, rather than empowerment through healing and personality enhancement. That’s why, despite what was institutionally viewed as several opportunities to “better himself,” Robert never stood a chance.

Robert was born in 1954 at Homer G. Phillips in the proud and de-facto segregated “The Ville,” the hospital’s name now usurped by speculator Paul McKee, the same man who kickstarted the gentrification of Robert’s once vibrant St. Louis Place neighborhood by selling 1000 acres to the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency.

Narrowly escaping death four times left Robert with scars: visible ones and those invisible—much too late for him acknowledged as PTSD. Robert was incarcerated from 2003 to 2008 and again in 2011.

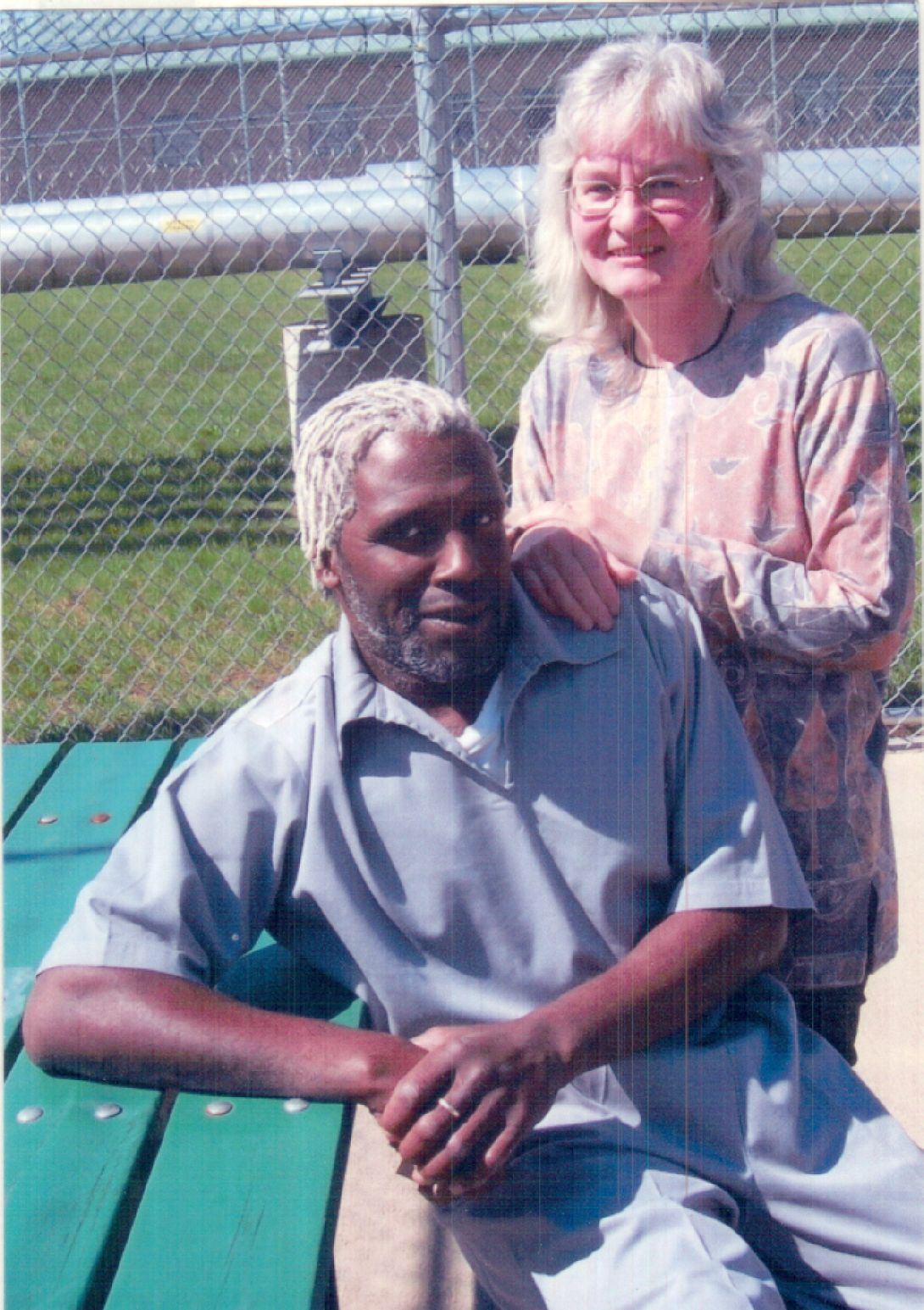

Affectionately known as “Wolf” or “Oil Can,” and, in later years as “Cotton Top,” a self-declared “Last Mountain Man” and “Tactitioner,” Robert was a free spirit, a volcano of energy, highly intelligent, well liked, respected and appreciated for his ever-present willingness to help and his compassion for the plight of others. He was always in high demand for his excellent work as a mechanic. A gifted, self-taught percussionist, Robert performed with Albert King, Bootsy Collins, Ice T and many local bands from the mid-1970s until the late-1980s, when decades of deliberate political and economic neglect and the “War on Drugs” took a toll not only on his decaying neighborhood but also on him.

Robert represents hundreds of thousands of Black men in the US who were railroaded to prison during decades of the “War on Drugs,” when police and prosecution tactics such as racial profiling, intense surveillance with targeted arrests through “buy-and-bust” and “stop-and-frisk” methods were increasingly—and to this day still are—used in deliberately redlined, disinvested and marginalized mostly Black urban areas slated for re-development that had been flooded with drugs.

“The White House is the Crack House and Uncle Sam is the Pusher Man” was a campaign initiated by the African People’s Socialist Party in Oakland CAL as early as 1982, protesting what would develop into a full-scale assault disproportionately targeting African Americans, despite surveys showing that they are no more likely to use and sell drugs than whites. Representing about 12% of the population, Blacks constituted 33% of all drug arrests and 50% of those serving time in state prison for drug offenses. Tough sentencing laws and policies blackmailed generations of non-violent drug offenders like Robert into accepting plea bargains that, to this day, result in long prison terms and render legal counsel virtually powerless.

Michelle Alexander: ‘The New Jim Crow – Mass Incarceration in the Age of Color Blindness’ (2012);

Marie Gottschalk: ‘Caught – The Prison State and the Lockdown of American Politics’ (2015)

“Three strikes” and other “habitual offender” laws, as well as stiff mandatory minimums enacted under the Clinton Administration—spearheaded by the current Pusher Man who now occupies the Crack House, Joe R. Biden Jr.—dealt a death blow to already struggling communities of color. Particularly the disparity of 100:1 (crack vs. powder) in cocaine penalties proved devastating. It was reduced to 18:1 under the Obama Administration and is currently under debate in the House of Representatives, dubbed “EQUAL Act” (Eliminating a Quantifiably Unjust Application of the Law). What would be “equal” about a—still doubtful—further reduction to 2.5:1 remains a mystery.

In 2011, Robert, tired from fixing a customer’s car, exhausted after walking a mile or two with his heavy tool box, dropped by a liquor store on Page Ave, in a blighted part of Wellston, a Black St. Louis County suburb not far from Ferguson MO. He was on his way home to adjacent U-City, where we had lived for more than a year. This stop, to buy a flask of whiskey lead to a sequence of events that ultimately took his life. What he did not know was the repercussions our move would have — away from dilapidated Dr. Martin Luther King Blvd on the western edge of St. Louis with jobless felons on every street corner to a nicer area — where he had hoped of making it through parole.

What Robert knew, but didn’t give a f*** about because it had been like this for all the 57 years of his life, was that he had three strikes against him: he’s a black male, comes from the wrong part of town and, on top of that, he’s self-determined—to his parole officer’s annoyance so head strong he did not accommodate her expectations of streamlined re-entry into society. He, who for decades had taken motors and transmissions apart, repaired them and put them back in with his mere hands, was stipulated to learn how to use a hammer at the Metropolitan Education and Training Center (MET). Needless to say: he fell asleep in class and dropped out.

What Robert did notice, but too late and with fatal consequences, was he was being closely monitored, targeted by police in an attempt to stem the tide of crime spilling over the city limit. Whether there was cooperation between his new, zealous parole officer—she was his daughter’s age and black—and the police, or whether the latter acted on their own account chasing success for an extra bonus, remains unclear. What is clear from court records is that the main characters in the game—a named, but never charged female (black) crack addicted informant and an unnamed (male and white) under-cover cop—set the trap, and Robert walked right into it, hoping for a ride home in exchange for a “little favor” so the guy could have a good time with his girl at an airport hotel (or so the story went). It turned into a “buy-and-bust” deal, his tool box worth a couple of hundred dollars seized by the cops.

That’s the prelude to the tragedy that got him another five years with plea bargain–could’ve been ten or fifteen without an attorney, given the fact that the ambitious prosecutor (female and white) charged him as a “persistent offender.”

Call it deferred justice or KARMA that seventeen years later she would lose her license over professional misconduct.

It was the “third strike” after a $50 crack deal and an “under-5-grams” marijuana deal ten years earlier in the neighborhood Robert grew up in. Helpful as he was, Robert was concerned the white guy who prowled his black neighborhood in search for dope could end up dead if he ran into the wrong people. It was a trap.

After decades of deliberate political neglect, economic depletion and incessant flooding with illegal drugs his neighborhood had turned from a once vibrant community into a ghetto with invisible walls. In all those years the police were never to be seen when needed. Now they were back. Their mission: sweep deteriorated parts of town clean in preparation for gentrification.

Robert’s neighborhood would fall prey to developer (more accurately described as ‘fence’) Paul McKee, who was tossed the whole area paying short to nothing, Robert’s father’s lots included that the family had unsuccessfully attempted to reclaim from the City’s LRA (Land Reutilization Agency) years before. McKee made good profit selling a huge chunk of it to the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency.

Robert’s two illegal drug busts got him a “120 days” drug treatment program in prison after languishing through half a year of continuances in the infamous Workhouse – the plea deal bargained by now St. Louis County Circuit Attorney Wesley Bell, back then still a P.D. who was just opening up his own private practice. Ten years “back-up time” in case Robert failed. The so-called “shock treatment” (meant to deter) ended abruptly one week before completion as the institutional parole officer, a white country girl and viciously racist in her deliberate falsification of facts to make him appear violent, wanted Robert locked up—despite the treatment counselors’ recommendation to release him. In her report she cited a conduct violation (alleged possession of a weapon) that Robert had been found “not guilty” of. Judge Ohmer (male and white) followed her recommendation and revoked Robert’s probation. I still remember all too well that it took me half a year to get Robert’s MODOC records disclosed, and the letters I wrote to the judge, the first two miraculously disappearing in the mills of justice, the last one hand-delivered to him in court. To no avail.

So there Robert went without due process, his case tossed back and forth in legal limbo between institutional and community parole officer, railroaded on an odyssey through the Missouri prison system, a nightmare not only for him but for tax payers as well. Robert’s experiences can be summarized as follows: “The key features of the US crisis in corrections—long before the financial crisis of 2008 hit—include: severe overcrowding, a lack of effective programming and treatment, the persistence of dangerous and deprived conditions of confinement, and the extensive use of forceful, extreme and potentially damaging techniques of institutional control.”

(Craig Haney, Journal of Law & Policy 22, 2006)

Nearly four years of warehousing under maximum security conditions (22 hours/day lock up) despite classified “custody level 4” went by before Robert even got the chance to do something that could justify the name “rehabilitation:” his GED. In 2005 he got kicked out of a boot-camp style “Therapeutic Community” drug treatment at St. Joseph, MO and was denied parole because he frankly voiced his opinion where mindless subordination was a ticket to success. On top of that Robert demanded respect, refused to be ridiculed as punishment for petty infractions like leaving his cup on the table, or a milk container on the window sill. In front of a sneering crowd of hip-hoppers who could have been his grandsons Robert had to stand on a chair and sing a song. He turned it into a satire. This ‘therapeutic’ intervention was called “push-up”—just another word for snitching. The ‘witnesses’, all white youngsters, were not only favored by the all-white staff, but, contrary to program rules, deliberately winked at when it came to ganging up and signing off on AA/NA-meetings that did not even take place. It was an indeed very therapeutic eye opener that caused a two-year set-back for parole.

CANCER takes seven to ten years to develop, depending on circumstances. It must have been gnawing on Robert ever since he was first locked up. Progressing age, years of coerced sedentary life style and malnutrition on a prison diet high in cheap carbohydrates and low in antioxidants, supplemented or replaced with over-priced prison commissionaire junk to avoid meals tampered with by other inmates, and staples overtly labeled “not fit for human consumption” (which he’d seen with his own eyes while assigned to kitchen duty)—all of this took its toll.

Upon release in September 2008 Robert was considerably overweight. Within a couple of months of being on parole, twenty pounds were gone. He was eating healthier and back to hard physical work as a “roadside mechanic” and the self-determined life he liked. Eventually his parole was revoked for “technical” violations: no progress finding employment, failure to report, testing “dirty.”

Back in prison since November 2011, Robert was placed in yet another all-white staffed boot camp style program, according to a counselor “one of our finest.” After four weeks he got kicked out.

While waiting to be sentenced for the last $50 crack deal, Robert lost significant weight, but did not even get a physical—not in 2012 at Fulton Reception, Diagnostic and Correctional Center (as name and purpose would imply)—and not in 2013. This fact is of significance since the Department of Corrections, in accordance with the Missouri Revised Statutes, RSMo 217.230, and the 8th and 14th Amendments of the US Constitution, claims to “ensure that offenders receive medical care that is equivalent to community standard.”

Robert had never been sick in all his life. For eighteen more months he ran baseball teams, won throwing horseshoes, gave prison concerts any chance he got, and participated in the weekly one-mile walk for inmates over fifty. That lasted until the summer of 2013 which would be his last. His body was supposed to function, no questions asked. But it didn’t, mistreated for too long with the only legal stuff abundantly available in prison (ironically highly addictive): sugar and carbohydrates. Underweight rapidly turned into overweight. Junk food fed the cancer, but he didn’t know that.

The heat at Algoa Correctional Center (which has no A/C) slowed Robert down. A vague, unknown pain came and went. One last time he fought off another prisoner’s attempt to kill him in the bathroom – the guy ended up almost drowned in a sink. Aware that he wouldn’t make it to his regular “12/12” outdate in September 2017 alive, Robert stopped going to the yard, to chow hall, even to the gym, where playing the Blues or Motown gave him peace of mind, taking him “home,” to another place, beyond the chain-linked fence with razor wire on top. He stayed in his cell, restricting himself to a sedentary lifestyle, eating junk food—all that not to risk his newly set parole date of March 18, 2014, hoping to avoid trouble with inmates who didn’t give a damn, and with mean and/or racist guards who routinely get more vicious by the day, the closer an outdate comes. He was caught between a rock and a hard place.

It took four weeks of suffering through increasing pain and loss of 20 pounds of overweight until, on September 21, 2013, Robert, already weak, dehydrated and malnourished, got in the long line of inmates seeking medical attention at what is called “open sick call.” Only to be told to come back the next day since the time was up.

It took another two months until, on November 22, he was declared a “medical emergency.” He’d been coughing up blood.

It took 10 days of waiting for the result of a useless x-ray taken at Jefferson City Correctional Center, the x-ray machine owned by CORIZON Health LLC, the for-profit medical contractor for MODOC. That’s easy money, reimbursed through the state prison budget with no questions asked.

It took an altercation with Robert’s institutional case worker (male, white) for me to learn that “nothing is wrong” with my husband, who was balling up in pain on his bunk, since CORIZON staff did not send him to the hospital, and Algoa Correctional Center’s warden (male and white) declaring he was “not in charge” and would be “happily” sued.

It took two more weeks, until, on December 6, 2013, Robert’s liver cancer the size of a baseball with metastases in both lungs was finally detected and confirmed through a biopsy, on December 9. For the very first time ever during the many years of incarceration Robert’s labs were drawn. The blood draw revealed a skyrocketing amount of tumor marker, as well as an infection with HEP A and B. Where from? Robert never messed with needles or tattoos, and he adamantly discouraged intimate relations between fellow prisoners. This leaves unsanitary prison conditions as culprits.

It took another week of fighting for his liquid diet with guards (male, white) who didn’t give a damn until Robert’s condition worsened to a degree that his medical score was finally raised and he was shipped to Tipton Correctional Center’s infirmary.

It took 10 days of CORIZON infirmary ‘care’ with an all-white staff for the bed bound man to develop a lung embolism that was only detected by chance, on December 23, during a lung biopsy at a local hospital. No precautions had been taken.

It took four weeks from diagnosis to the “staging” of his cancer on January 3, 2014—anxiously awaited since “stage 4” meant eligibility for medical parole – and the community oncologist Dr. Hopkins (female, white) ordering chemotherapy.

A CT scan that could have determined Robert’s extremely limited life expectancy, therefore further underscored his eligibility for release as the cancer had meanwhile spread to his colon and bone marrow and ascites had developed, was not done until the day of his death. The procedure would have decreased CORIZON’s profit margin.

It took another 10 days until Robert received the cancer drug, because, according to CORIZON Director of Nursing (female, white), it was “hard to get.” In reality the expensive treatment was delayed until after the Parole Board decision. On second thought, it was indeed “hard to get” as CORIZON Regional Director (male, white) had to sign off on it. He also discarded Robert’s right to a second opinion as “not warranted.”

It took three days for the CORIZON doctor at TCC to submit his – to this day undisclosed—recommendation, supposedly based on the also withheld oncologist’s report. The only CORIZON statement found in the hard copies of Robert’s medical records was the so-called “Karnofsky scale” that described him as still “able to feed and care for himself”, the lower part blank where additional information should have been provided. The CORIZON doctor thus blatantly violated RSMo 217.250, which stipulates the following:

“Whenever any offender is afflicted with a disease which is terminal, or is advanced in age to the extent that the offender is in need of long-term nursing home care, or when confinement will necessarily greatly endanger or shorten the offender’s life, the correctional center’s physician shall certify such facts to the chief medical administrator, stating the nature of the disease. The chief medical administrator with the approval of the director will then forward the certificate to the board of probation and parole who in their discretion may grant a medical parole or at their discretion may recommend to the governor the granting or denial of a commutation”.

Understanding and navigating this maze of procedural stipulations was a challenge that not only consumed valuable time that Robert did not have, but also turned into a bureaucratic, traumatizing ‘passing the buck’ run-around.

It took three more days until, dated January 9, 2014, the letter of denial of medical parole was written, despite (or maybe due to?) the tenacious advocacy of Robert’s attorney Randall Cahill in cooperation with Missouri State Senator Jamilah Nasheed.

Releasing Robert would have saved the prison budget tens of thousands of dollars. Furthermore, the Missouri Department of Corrections was aware that, as his wife, my private health insurance would have covered his treatment in the community.

It took another six days until, on January 15, 2014 Robert received the notification of denied medical parole. Then he was officially transferred to Tipton Correctional Center, where he had been “technically” languishing on “sleeper status”—no access to his personal belongings, no comb, no dentures, no music tapes, no envelopes and stamps, no pictures of family and friends, denied even my Christmas card to him—for four, long weeks. According to assistant warden Webber (female, white) my letters turned up “in his file” after Robert’s death.

After another routine chest x-ray Tipton Correctional Center declared Robert fit for—yes: kitchen duty. Four days before his death. Ironically, he was confined in a negative pressure infirmary cell as his labs had shown a HEP A and B infection.

Now, without—ever—receiving a “true” reading of his tumor marker (it would have cost extra money) in order to see whether Robert’s ravaged body could even withstand the ordered chemo onslaught, without consideration of his progressed anemia and already severely compromised immune system (he suffered from internal and external bleeding and had developed a thrush) Robert was then given Sorafenib—without CORIZON consulting with the oncologist. After all, Dr. Hopkins would have found out about the two-week delay. The cancer drug pushed Robert over the edge.

During the roughly eight weeks of Robert’s ordeal, I was constantly on the phone to advocate for him and monitor what CORIZON staff did with (to) him. Because of this Robert was harassed by CORIZON Director of Nursing (female, white) to a degree that he almost withdrew his consent for Release of Medical/Health Information (HIPAA) to me, feeling held hostage.

For eight nightmarish weeks during which CORIZON ‘Chronic Care’ staff did nothing but monitor Robert’s decline, I was given the run around, traumatized by incessant assaults of misleading and/or conflicting information, half-truths and deliberate lies until the very end. I still vividly recall that after the chemo started, I received outdated lab results, was advised there were “no major changes” when Robert needed oxygen due to the progressed anemia that officially did not exist. His condition was even downplayed on the day before his death, when, instead of being able to visit, on Friday, January 17 Robert had been rushed to the hospital, all of a sudden “qualifying” for ICU care after weeks of deliberate neglect and malpractice, whereas in the morning I had been told he was “stable” and it was okay to visit. So, instead of seeing Robert alive for what would have been the last time, I ended up confronting CORIZON Health Service Administrator Marilyn and TCC assistant warden Webber, advised by the former, he “just needed a little hydration and a blood transfusion” and would be back after the weekend, the assistant warden graciously extending Robert’s sisters’ visiting permit to the following weekend.

Robert passed away on Saturday, January 18, 2014, isolated from his caring family, tortured—I spare you the details to preserve his dignity as a man, but there’s a haunting parallel to the Jim Crow days. He died shackled and chained to a hospital bed at St. Mary’s in Jefferson City, in the last two hours of his life ironically allowed self-administered morphine as much as he needed, a drug he never wanted to use in his whole life.

Who is to blame for Robert’s inhumane death? Likely it’s a well-established cooperation, a collusion of motives re-enforcing each other. It can reasonably be assumed that the oncologist does research. Considering her indifference under what conditions Robert would die, and given the incessant flow of van loads of helplessly exposed, dying long-termers from JCCC, the maximum-security prison in Jefferson City, who receive chemo and/or radiation at local hospitals under her supervision, it feels like the infamous Tuskegee experiment revisited, because: what value has “informed consent” under prison conditions, with a second opinion denied?!

CORIZON, on the other hand, obviously had no interest in letting a valuable cancer patient go. 24/7 infirmary service means: big money. BIG money. This then is the consequence of out sourcing services to private companies. Robert’s premature death at age 59, roughly eight weeks after diagnosis of cancer, is caused by Missouri Department of Corrections and the private health company’s deliberate indifference and—not surprising—CORIZON’s single-minded focus not only on making money, but on exacerbating profits through medical negligence and malpractice.

What happened to Robert occurs on a daily basis to prisoners throughout the United States. Looking at Robert Rowry’s fate and beyond, it is obvious what needs to change. The Prison Industrial Complex has to be abolished. Period.

Short of this long-term goal, the list of reforms which would at least alleviate the conditions for those trapped behind bars is long and likely incomplete, but this is what comes to mind:

- Repeal drug laws, de-criminalize all illicit drugs while expanding job training, livable employment and culturally centered drug treatment opportunities in the community;

- Overhaul the ubiquitously prevailing stupidity of ‘Law & Order’;

- Reverse militarization of the police and police tactics that deliberately target communities of color (‘hot spot policing’, ‘stop & frisk’ and ‘buy & bust’);

- Establish Civilian Oversight over police departments to end arbitrary arrests, killings, abuse, free casing and entrapment;

- Paradigm shift for the prison system: away from warehousing towards genuine rehabilitation (as in the 1960s and 1970s), with educational and vocational opportunities, empowering classes for personality enhancement, (trauma) psychotherapy, etc. in every prison;

- Diversification of staffing, cultural competency as hiring requirement (DOC and for outsourced services);

- Prison closures as the only means of effectively reduce state budgets; drastically decrease incarceration in favor of creating supportive communities that naturally deter negative behaviors;

- Focus on prevention: Drop-In Centers (an unstructured, ‘low-level’ approach for young people who fall through the cracks of traditional youth work), action-oriented youth projects that serve the community;

- Abolish ‘adult crime – adult time’ idiocy: the young brain does not mature until age 25!

- Establish independent Civilian Oversight for all prisons/jails, including oversight over medical/food services and dietary needs;

- Stop outsourcing of medical services, provide medical care through local physicians and/or community clinics with sufficient funding;

- Paradigm shift for institutional drug treatment programs: away from mindless subordination towards strengthening self-esteem through character building;

- Restore civil and human rights upon re-entry (voting rights), abolish any form of discrimination of ‘ex-offenders’ (‘The Box,’ denial of foods stamps and other benefits);

- Provide access to adequate, affordable housing (including HUD), free educational/vocational and/or job opportunities with livable wages upon re-entry;

- Abolish court fees and ‘intervention fees’ for people on probation or parole;

- Provide a variety of trauma therapeutic intervention options in the community, for victims and perpetrators alike, according to their needs.

- Acknowledge the fact (but that’s probably asking too much of mainstream America) that much of young people’s angry, provoking and ‘anti-social’ behaviors are simply a reflection of what they experience. One rap song that Robert accompanied with his guitar play in prison was titled: “You live what you learn! “

From 2014 to 2018, when I took on the daunting task of Missouri CURE Prisoner Health Committee Coordinator, I documented more than 250 cases of often severe violations of Missouri Statute 217.230, which stipulates that medical care for prisoners should stress “health care education, disease prevention (!), immediate (!) identification of health problems and early (!) intervention to prevent more debilitating chronic health problems“, with the declared goal “to return offenders to the community as medically stable as possible, so they may become productive citizens of the state”.

The reality is: prisoner medical neglect by Corizon Health LLC, ranges from delayed diagnoses and treatment of all kinds of illnesses (even contagious ones such as HIV, Hepatitis A, B, and C, Staph or MRSA) to withholding necessary medical care such as specialist encounters, diagnostic exams, and surgical procedures that are deemed “unnecessary” or “elective”. Denials or delays very often cause irreparable harm. Deliberate or negligent misdiagnoses of life-threatening illnesses such as heart attacks and cancer are rampant. Even prisoners who, after months or even years of filing grievances, “qualify” to see a community specialist, are then advised that the Corizon Regional Director makes the “final judgement call”. Several reports state that, hours after the initial neglect, prisoners had to be “flown out by chopper” to save their lives. Corizon Health LLC ‘Standard Operating Procedures’ not only cause increased long-term costs for taxpayers – when those prisoners are lucky enough to survive and become ‘chronic care’ patients – but also result in horribly high numbers of avoidable deaths.

About 100 of the most egregious cases of Corizon’s malpractice and deliberate indifference were addressed with MODOC Health Services, requesting their investigation and intervention to rectify prisoners’ concerns as it is MODOC contract monitors’ explicit assignment to “monitor” Corizon. With very limited success, as was to be expected.

I came to the conclusion that RSMo 217.230 is an oxymoron: for-profit medical providers like Corizon Health LLC are not suited to provide the medical care stipulated by this state law due to their primary focus on increasing profits through reduction of operating costs. Prisoners would be better served by a community-based system of care that encompasses the enrollment of all prisoners in Medicaid (as an intermediate measure until we accomplish universal health care for all).

This would allow for greater public oversight, potentially alleviating some of the most egregious abuse and save some prisoners’ lives even though obviously not addressing the root causes.