AN EXTREMELY IMPORTANT sector of the population is almost never recognized in the so-called culture wars over book banning. This is the active reading of old and new banned books by “ordinary people” largely ignored by banners and the educated alike.

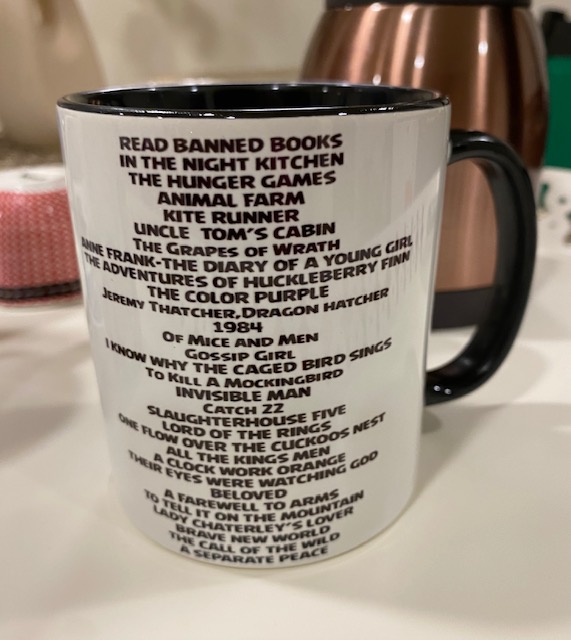

I have come to know this large group, which shatters expectations and stereotypes, in part through their reactions to seeing me in one of my four “Read Banned Books” and “I’m with the Banned” t-shirts and sweatshirts.

This occurred first with a new plumber, a now middle-aged high school dropout. When Anthony first came to my house on a service call, he stopped at the door to read the front of my t-shirt with a list of mainly 20th century banned books. He asked me to turn about so he could read the back of my shirt.

Anthony was excited. He had read and appreciated all of them, some in school, many after he left school and became a manual tradesman. We began a several days’ conversation. He was surprised and angry to learn about current book banning.

A more recent interaction was with our master furnace repair person, responding to my “I’m with the Banned” sweatshirt upon entering our house. John grew visibly excited. He first read all the listed books in his Advanced Placement English and American History courses. He loved them and reread them; he saw that his children did the same.

I quickly recovered from my initial surprise that a highly skilled furnace engineer had successfully completed AP courses and loved to read the best literature. After we shared our memories of reading, he admitted his own outrage at today’s book banners and their damage to the young.

More recently a young woman checking my house as a Terminix pest inspector, also a mother of a six-year son, began a wide-ranging conversation after reading my shirt. She came inside to look at and then photograph my collection of the best recent diverse illustrated children’s books in order to find them for her son and nephews.

My shirts also prompt immediate and enthusiastic reactions from salespeople and clerks in stores, and order takers and servers in restaurants. They too are familiar with prominent works of literature. They are eager to chat. They read.

Together, these responses underscore the imperative need to correct the almost reflexive neglect and often the negative stereotypes of “ordinary people” and their reading. We need to add them to our images and understandings — plural.

The Book Banning Plague

Since 2021 when the current, uncontrolled waves of book banning broke their historical boundaries, the combined actions and inactions swing between two poles with no apparent ground between them. Both are versions of the dangerous “literacy myth” that I identified in 1979 with my book of that title.

On one side, most often reported, is the right-wing censorship campaign coordinated by a startlingly successful social media and website campaign funded by the Koch brothers, Heritage Foundation, and other more or less familiar billionaire-funded groups. Their active agents include the so-called “Moms for Liberty,” who are actually Moms Against Literacy and the rights of their own and other peoples’ children to read and grow up.

Media, school board meetings and state legislatures overflow with uninformed social media-fueled talk about banning (or not) books that are claimed to violate always unspecified boundaries. The range is endless, from never-defined profane to obscene; uncomfortable; influential, age, gender, race, or otherwise inappropriate; suggestive images that are typically cartoons — all somehow but never clearly leading to sex or transsexualism.

Since none of the banners show any familiarity with the actual contents of the literally thousands of books they seek to remove from ready access — including ordinary dictionaries — I renamed them the New Illiterates. They remain ignorant of the simple fact that any young person with a cellphone, tablet or laptop can access almost anything.

Today’s banning campaigns are historically unique. Other book-banning movements, beginning in antiquity and often associated with orthodox religious crusades against reformers, actually read what they sought to ban.

Notable examples were the Roman Catholic Church’s efforts to suppress Martin Luther’s Reformation; through Anthony Comstock’s late 19th century efforts to block “obscene materials” — birth control information — from the U.S. mail; and the 1950s-1960s now seemingly humorous “Banned in Boston” efforts.

Instead, today’s book banners and the state politicians with whom they work produce lists of thousands of books to be proscribed or, in the words of one Texas state legislator, “to be investigated” with no criteria.

The lists are based on google word searches, with all almost all banned authors being men and women of color and/or LGBTQ. Heterosexual white male authors only appear if their novels have LGBTQ protagonists. Free-thinking respondents who propose banning the Bible make a stronger case than the organized banners.

Children’s Rights to Grow

Against more than a century of efforts to establish children’s rights, including the right to grow up and mature, the book banners campaign for regressive “parents’ rights,” doing all in their power to obstruct their own children’s learning and maturity in all spheres of their development.

All reputable research and legitimate observers, including the young themselves, agree that reading “challenging” and “uncomfortable” material is central to social and personal maturity.

On the other hand, are the so-called “free speech absolutists” who draw no distinctions between any level of appropriateness, or the responsibilities of legal, knowledgeable and ethical agents from teachers and librarians to parents and the young themselves.

Missing in these narratives are major areas of cultural and intellectual action in between these poles. As one now 23-year recent college graduate friend told me: when “I was about eight, if I were reading a book that made me feel uncomfortable, I would simply put it down and stop.”

Also missing from the obsessive focus on child readers as isolated, vulnerable and potentially violable individuals is the active role over time, and especially today, of book clubs in and now especially out of school. In fact, the major collective actions in combatting book banning efforts on all levels today are teen book clubs, especially in right-wing restrictionist Texas and Florida.

With the advice and aid of librarians and teachers, and often the provision of books by bookstores, authors and publishers, these are some of the most exciting places of group actions including reading and discussion: mutually interactive learning.

Recent studies suggest that more young people are reading—and buying — printed books, rather than relying on online texts. Here’s another trend to fill out our images. How easily we forget the agency, indeed the sources of growth and maturity of the young themselves!

This is why it is absolutely critical that all means and points of access including public libraries, bookstores and publishers — and readers of all ages — be freed from efforts to remove their human and Constitutional rights. These parts together form a larger, more complex, and richer world of reading and uses of literacy.