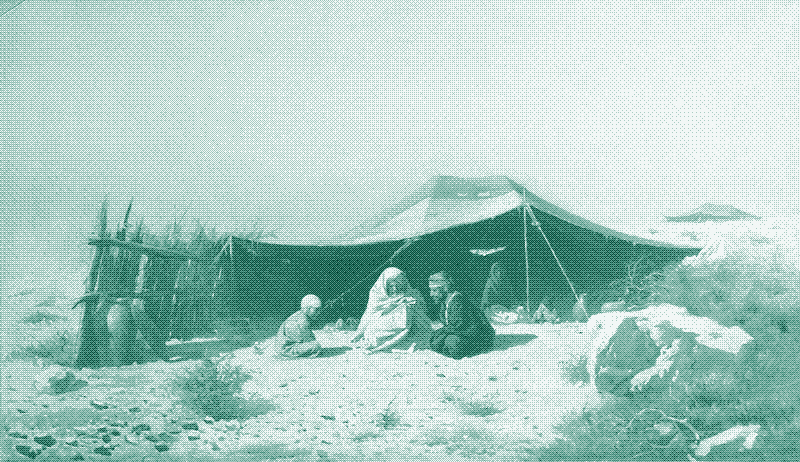

Image: “Arabs in the desert”, a painting by Vasili Veresjtsjagin. End of 19th or early 20th century. Image in the public domain. Inside the tent, temperatures could be up to 10-15 degrees Celsius cooler than in the surrounding atmosphere.

Thermal insulation is a cornerstone of policies aimed at reducing the high energy consumption for heating and cooling buildings. 1 In many industrialized countries, building energy regulations require new and existing buildings to have insulated walls, floors, and roofs, as well as double- or triple-glazed windows. In cold weather, insulation slows down the heat loss from the interior to the exterior, reducing the energy use of the heating system. In hot weather, insulation delays the transfer of heat from the outside to the inside, thereby reducing the energy consumption of the air conditioning system.

Modern insulation methods involve the permanent addition of non-structural materials with high thermal resistance, such as fiberglass, cellulose, or mineral wool, to the building surfaces. Viewed in a historical context, this approach is unusual and stems from a shift in architectural style. 2 Preindustrial buildings often didn’t require extra insulation because they had a significant amount of thermal mass, which acts as a buffer to outside temperature fluctuations. Additionally, the building materials themselves could have high thermal resistance.

Viewed in a historical context, modern insulation methods are unusual and stem from a shift in architectural style.

For example, in the 12th and 13th centuries, Northern Europeans built thatched houses with straw roofs that were 60-80 cm thick. Walls were often built of clay and straw, which provided excellent levels of both thermal mass and thermal resistance. 3 In contrast, modern buildings are frequently steel and concrete structures that have very little thermal mass. Consequently, they are very sensitive to outside temperature fluctuations.

Furthermore, preindustrial buildings had few and small windows, which were often unglazed and closed only by sliding shutters at night. 4 On the other side, modern buildings have large glass surfaces, which results in significant heat losses in winter and high solar heat gain in summer.

In hot climates, buildings were also designed for maximal ventilation, for example, through the use of courtyards and building orientation. 5 By contrast, modern buildings often resemble one another, regardless of the local climate. All this results in high energy use for heating and cooling, so we add insulation and double-pane windows, especially since the oil crises of the 1970s.

Permanent versus Removable Insulation

A return to vernacular buildings, which maintain interiors at a comfortable temperature through architectural design rather than energy-intensive technical installations, could significantly reduce energy consumption for heating and cooling. However, it’s not a short-term solution: it would require a large amount of time, money, and energy to replace the existing building stock.

Fortunately, history offers an alternative solution that can be deployed more quickly and with fewer resources: textiles. Before the Industrial Revolution, people added a temporary layer of textile insulation to either the interior or the exterior of a building, depending on the climate and the season. In cold weather, walls, floors, roofs, windows, doors, and furniture were insulated with drapery and carpetry. In hot weather, windows, doors, facades, roofs, courtyards, and streets were shaded by awnings and toldos.

Removable insulation can achieve significant energy savings with much more flexibility than permanently enclosed insulation materials. Because modern insulation methods require construction permits and structural interventions to a building, they are expensive, time-consuming, and only accessible to home owners. Furthermore, modern insulation methods are ill-suited for older buildings, in which case they are often not financially and energetically sustainable. 67

People can often install removable insulation without obtaining building permits or hiring professionals, making it an affordable do-it-yourself solution within reach of everyone.

In contrast, removable textile insulation is suitable for both new and existing buildings, as well as for renters and owners alike. People can often install removable insulation without obtaining building permits or hiring professionals, making it an affordable do-it-yourself solution within reach of everyone. Removable insulation can be applied quickly and without causing a nuisance to residents and neighbors.

For cooling, textiles have another advantage. Airtight buildings with a permanent insulation layer may overheat dramatically if the electric cooling system fails during a heatwave. 8 In contrast, awnings and toldos can keep interiors comfortable independent of an electricity supply.

Winter: Carpets and Curtains

Historically, the use of removable textile layers followed different approaches depending on the climate. In cold regions, for example, in large parts of Europe, people installed various textile “devices” on the interior building surfaces to increase thermal comfort. Some of these, such as curtains and carpets, can still be found in modern interiors, although not to the same extent as they were used in earlier times.

For example, carpets were not only laid on floors but also hung on walls (“wall carpets” or “wall hangings”), draped over tables (“table mats”), and used on other furniture. Likewise, thick curtains were hung in front of windows but also doors (“portières”) or door openings and mounted around beds (“bed canopies” or “bed hangings”). 910111213141516 In some regions, people suspended thick fabrics, such as duvets and quilts, from the ceiling during the winter months. 171816

These “home fabrics” were usually made of natural wool, still one of the best-performing insulation materials. 19 The thermal resistance of wool remains the same whether it’s permanently enclosed in building surfaces or hung in front or laid on top of them. Floor carpets and wall hangings thus slowed down the heat transfer from the inside to the outside of the building, just like modern insulation methods do. Likewise, a set of wool curtains 2-3 cm thick gave a single-glazed window the insulation value of a modern double-glazed window. 20

Before the 18th century, Europeans imported oriental carpets but only used them on walls and furniture because they considered them too precious to walk on.

The production of wool rugs and carpets by flat weaving and, later, by knotting dates back to at least the early centuries AD in the Middle East, Central Asia, and the Far East. However, wool floor carpets only became commonplace in Europe around the 18th century, when carpet production was mechanized. Before that time, Europeans imported oriental carpets but only used them on walls and furniture because they considered them too precious to walk on. For floor insulation, they used animal skins, loose straws, or “rush mats” made from grasses. 1112132122

Home textiles also stopped draughts coming in through cracks in building surfaces and window and door frames. 9 That is the reason why window curtains evolved to open from both sides. Two-sided curtains can be open, providing daylight and a view while stopping draughts that enter through the poorly sealed joints between the wall and window frame. 1011

Two-sided curtains can be open, providing daylight and a view while stopping draughts that enter through the poorly sealed joints between the wall and window frame.

During winter, thick and heavy curtains could shield a space from the cold air coming in everytime someone opened the door. Such “portières” can still be found in the entrances of historical public buildings or cafés, but they were common in family dwellings as well. 10111716

Fabrics also increased comfort in ways that modern insulation methods cannot. Floor carpets slowed down the conductive heat transfer from the feet to the cold floor, while table mats brought arms and hands in contact with a warmer surface. Duvets hanging from the ceiling, bed hangings, and table mats all accumulated heat from the human body or another heat source in a smaller space. 171816

Upholstered Chairs, Wainscoted Walls

Textiles could also be combined with woodwork to the same effect. For example, the folding screen was a work of tapestry and carpentry that blocked draughts and reflected radiant heat from a fireplace. 9 Upholstered chairs, which appeared at the end of the 1600s, had a cushion encased in the covering material and were padded with feathers, wool, horsehair, down, or rags. 12 They provided a softer seating surface but also reduced the conductive heat loss from the body to the furniture. 9 Pillows also contributed to thermal comfort.

Some decorative devices, consisting of wood or plaster, fulfilled similar functions to textiles. For example, molding stopped draughts and was used to cover joints between walls and floors (baseboards), ceilings (crown moldings), and doors and windows (casings). 923 Some houses had wooden partitions hinged to the ceiling that were let down in winter to concentrate warmth around the fireplace. 24

Molding stopped draughts and was used to cover joints between walls and floors, ceilings, and doors and windows.

Wainscoting was a type of oak or pine wood paneling typically installed over a wall’s lower portion, a practice that dates back to the late Middle Ages. 91225 Such wooden paneling could also be upholstered, further increasing its thermal insulation value. Interior shutters could replace curtains. Box beds were closed on all sides by panels of wood, substituting for bed hangings.

Unfortunately, there is very little academic research on the potential energy savings of home textiles and similar devices, whether used alone or in combination with permanent insulation. There is a handful of older studies that calculate the insulation values of floor or wall carpets, but none examine the combined effects of interior fabrics and other decorative elements. 26

Summer: Awnings

The home textiles described above were primarily used to improve thermal comfort in cold weather. The exception is the window curtain, which not only keeps heat indoors during winter but can also keep solar heat out in summer, resulting in a cooler environment. 27 However, for cooling purposes, window textiles are much more effectively used on the building’s exterior in the form of an “awning,” which blocks solar heat before it enters through the glazing. 28

In Europe, both window curtains and awnings only emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries, when glass became affordable enough to allow for larger areas of glazing. 101221 As mentioned, larger windows complicate the heating and cooling of buildings. Still, they also have advantages: they provide free solar heat in winter, increase natural ventilation, offer a better view, and allow for daylight throughout the year. 22729

Window curtains and awnings – the latter usually made of canvas – can reconcile all these concerns. For example, an awning can block solar gain in the summer while keeping the window open for ventilation and continuing to provide a view and lighting. 30 In the 19th and early 20th centuries, European and North American cities were dressed in awnings. Several skyscrapers in New York City and Chicago originally had them, too. 31

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, European and North American cities were dressed in awnings.

Awnings and air conditioning can be combined, resulting in a significant decrease in energy consumption. Several studies show that awnings can reduce the energy use of air conditioning systems by one-third to more than one-half of the total, yielding energy savings that surpass those of more expensive double-pane or low-emissivity glazing (which is designed to block UV rays). 832333435363738 Nowadays, windows are larger than ever, and so awnings can obtain very good results for a relatively small investment.

Summer: Toldos

Outside of Western Europe and North America, the use of exterior “curtains” for cooling predates the use of glass windows by many centuries. For at least 2,000 years in the Middle East and around the Mediterranean, people used textiles not only to shade (unglazed) windows and doors but also roofs, facades, courtyards, and entire streets. Such textile furnishings are known as “toldos” or “sun sails.”

The classical toldo, made from hemp canvas, is a rectangular or triangular, curtain-like awning suspended by sewn-on eyelets on parallel wires. 39 Micro perforations avoid the stagnation of warm air underneath the shading device. 40

In Ancient Rome, sailors assembled large “velaria” to shade amphitheaters. 394140 In Cairo, Egypt, street and courtyard canopies, or toldos, still characterize the cityscape, especially in some historic neighborhoods. 39 European cities with Islamic roots, such as Córdoba, Málaga, Granada, and Seville in Spain, continue to use or have revived the use of street toldos that span entire city streets and districts.

Although toldos have been used predominantly in desert climates, climate change makes them increasingly useful for temperate climate regions as well.

A 2020 study in Cordoba showed that street toldos decrease the temperature of pavement surfaces, building facades, and roofs by up to fifteen degrees Celsius. 40 Collective shading could thus replace individual awnings, but the cooling effect on buildings depends on street orientation. Although toldos have been used predominantly in desert climates, climate change makes them increasingly useful for temperate climate regions as well.

Unlike air-conditioning, awnings and toldos are robust, low-cost, and technically simple solutions within reach of most households and societies. 40 In Egypt, rather than a top-down development initiated by authorities, toldos are made and installed by residents in a “demonstration of an architectural bottom-up movement supported by a local industry of expertise and craftsmanship.” 39

Covered Streets

The boundary between removable and permanent insulation is not rigid on the outside, either. For example, louvered wooden shutters or architectural interventions such as recessed windows and covered galleries can replace awnings and toldos. 42

Residential streets in Islamic cities could be either partially covered by cantilevered buildings or totally by additional living spaces. Shopping streets were often completely covered, either heavily by perforated vaults, semi-heavily by high parapet walls and double-pitched roofs, or lightly by thick planks and reeds. 42

Trees can also serve as awnings and toldos. Deciduous trees shade buildings and streets in summer while allowing the sun to pass through in winter. However, trees take decades to grow and need water as well, which is often scarce in the regions where toldos have been used traditionally.

![Image left: British Counsel Building 1917. People in the hot, arid climate in the Red Sea region have traditionally used an elaborately carved wooden window screen called a “masharabiya” (Egypt), “rowshan” (Saudi Arabia) or “jali” (India, Pakistan). [^11][^28][^36] It consists of a wooden lattice structure that juts out into the street and covers a single window or multiple windows from the top to the bottom of the building. “Shishes”, woven grass or reed mats hung in windows and doorways, were the more affordable version for less wealthy people. Image right: Street Scene 1916. Photo credit: [^36].](https://solar.lowtechmagazine.com/2025/06/dressing-and-undressing-the-home/images/dithers/roshans_dithered.png)

To finish reading the article/manual on

“How to Dress and Undress your Home”

click on …

https://solar.lowtechmagazine.com/2025/06/dressing-and-undressing-the-home/

and you will find information about tents and other low energy methods of home

temperature control.