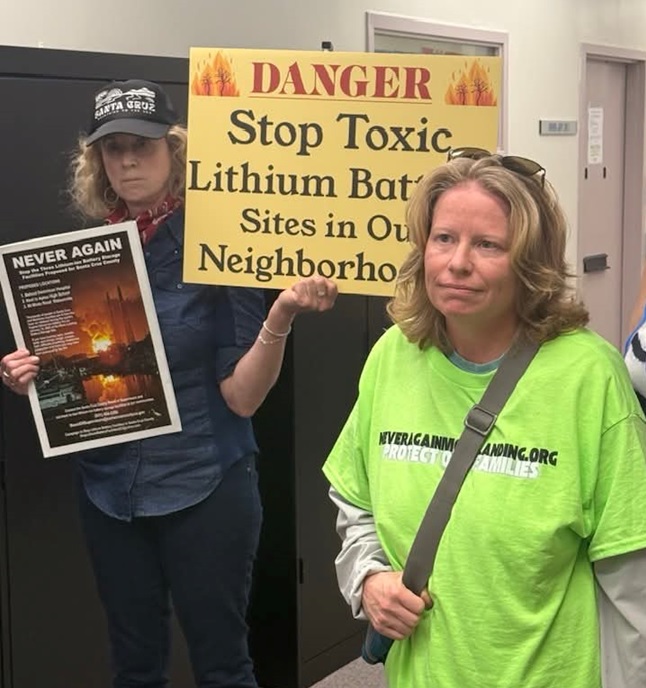

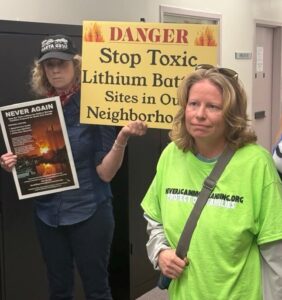

Angie Roeder, photo by Matt McFaul

In 2022, Brian and Angie Roeder bought a five-acre farm near Brian’s childhood home in Monterey County, California. Monterey County grows most of the USA’s lettuce, the world’s artichokes, and substantial amounts of our broccoli, spinach, cauliflower and strawberries. The Roeders’ forever home has fruit trees, barns for pet pigs, a greenhouse and a solar PV system.

While out on their back deck on January 16, 2025, the couple saw towering, 250-foot flames emerge from Moss Landing: Vistra Corporation’s battery energy storage system (BESS), the world’s largest BESS facility, was on fire. To protect people from inhaling the batteries’ toxins (cobalt, nickel, lithium, manganese, PVC, PFAs, etc.), Monterey County officials ordered nearby residents to evacuate. They closed Highway 1, the area’s schools and 500 businesses. The Roeders, seven miles from the fire, were not required to evacuate; but out of concern for their young son, they quickly left for San Francisco.

Within a few days, 80% of Vistra’s approximately 4.5 million batteries went up in smoke.

On January 17th, the day after the fire started, Monterey County officials lifted their evacuation order. Three days later, the BESS facility fire extinguished itself. Four days after testing around the facility, The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced that it found no detectable threats to public health.

For nearly a month, while debris smouldered, neither state nor county officials notified the medical community about the fire’s potential health effects. When residents or their animals got sick, they did not know where to turn.

A HISTORY OF BESS FIRES

Because solar and wind systems generate energy only while the sun shines or the wind blows, users who expect electricity 24/7 rely on backup from the power grid—or a battery energy storage system. BESS facilities store electrical energy in relatively inexpensive lithium MNC (manganese, nickel and cobalt) batteries, and release the energy at night, on windless days or during power outages. Proponents claim that BESS systems help reduce our reliance on fossil fuels. While this is a worthy aim, the Moss Landing fire intensifies questions about reducing battery fire hazards and the ecological impacts of mining battery components.

The Vistra BESS at Moss Landing opened in 2020. By 2023, it reached a 3GWh capacity. (One gigawatt hour can power about one million homes for an hour, depending on households’ use of energy-intensive air conditioners, video games, EV chargers, etc.)

When lithium batteries are repeatedly overcharged over time, say beyond 80%, they become unstable. This can lead to “thermal runaway,” a chain reaction of multiple fires and/or explosions so hot that nothing can extinguish it. It has to burn itself out. Dousing a thermal runaway with water is ineffective and can cause a chemical reaction.

In 2021, only a few months after opening, and again in 2022, when a sprinkler system malfunctioned, Vistra’s Moss Landing BESS overheated and caught fire. These fires were extinguished within a day of outbreak.

The Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), a nonprofit funded by energy companies and various government offices, began keeping a database of BESS failures and fires in 2018. It shows that the number of new BESS facilities have increased exponentially, causing the rate of fire and other failures to decrease. However, the overall number of fires has increased—with increasingly devastating impacts. In Jefferson County, NY, a battery energy storage system caught fire three times in 2023. More recently, BESS facilities have caught fire in San Diego, Escondido and Arizona. In May, in a residential area in North Ayrshire, Scotland, a battery recycling plant exploded.

Vistra will not disclose their batteries’ exact numbers or contents—they call this “proprietary” information. Based on calculations that he’s seen from available information, Brian Roeder estimates that during the fire, the facility probably emitted 5,000 tons of metals, dioxins and PFAs (forever chemicals).

The Vistra BESS fire at Moss Landing, January 26, 2025.

EFFECTS THAT EPA FAILED TO MEASURE

When the Roeders returned home, two days after the fire started, Angie experienced headaches, shortness of breath and a metallic taste in her mouth. She started a Facebook group, Moss Landing Power Plant/Vistra Fire Symptoms to connect with others who had become ill. Eventually, more than 4,000 people signed up. They had symptoms like Angie’s, along with worsening of existing ailments, persistent sore throats, bloody noses, migraines, difficulty swallowing and blistering skin. Animals had also become ill, and animal stillbirths had increased.

Two weeks after the fire, wanting to know what toxins it released and what the long-term effects could be, the Roeders and some of their neighbors founded Never Again Moss Landing (NAML). Michael Polkabla, an industrial hygienist, suggested that people test for residual toxins by wiping outdoor, non-metalic surfaces with “ghost-wipe” tissues, a verifiable controlled method. Adhering to “chain-of-custody” protocols to ensure their samples’ legal validity, Brian Roeder assembled, distributed and collected 124 kits and sent them to ALS, a testing lab in Salt Lake City.

Meanwhile, Dr. Ivano Aiello, a scientist at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories and department chair of geological oceanography at San Jose State, took topsoil samples from the Elkhorn Slough Reserve, immediately adjacent to Vistra’s BESS facility. This seven-mile stretch of wetland marsh with winding tributaries connected to Monterey Bay hosts more than 700 species of plants and marine life, including pelicans, sea lions and (threatened) sea otters. For a decade, Aiello has studied how to remediate this estuary, which has been exposed to pollution from the Moss Landing power plant since it was built in the 1950s. His pre-fire tests provided a critical baseline for comparing topsoil samples before and after the fire.

Aiello sent his samples to California’s Department of Toxic Substances Control.

The Elkorn Slough Reserve, with Vistra’s power plant in the top left.

THE STUDIES’ RESULTS

There’s never been a BESS fire of Moss Landing’s size or magnitude—or, because of NAML’s citizen-led, community-wide effort, a test of samples so geographically widespread. The Never Again Moss Landing group sampled surfaces up to 40 miles from the fire. According to the ALS Lab, their samples showed heavy metal surface deposits increased from less than five parts per billion (PPB) before the fire to as much as 690ppb after the fire.

These findings correlated exactly with Dr. Aiello’s findings. His post-fire samples showed hundreds to thousand-fold increases in concentrations of nickel, manganese and cobalt—materials used in lithium-ion batteries. Toxic to aquatic species and humans, these heavy metals will chemically transform as they move, potentially, through our food web—and could endanger it.

How could NAML’s and Dr. Aiello’s samples turn out so differently from the EPA’s findings? When a thermal runaway fire burns (at up to 5000 degrees Fahrenheit), toxic metals and dioxins are not destroyed. They vaporize into a mist and blend with moisture in the air. They become too small for some instruments (like the ones that EPA used) to measure.

When the Moss Landing fire started, the EPA immediately tested the ground for hydrogen fluoride, a chemical so toxic that exposure to one drop can maim and kill. However, aerosolized hydrogen fluoride is lighter than air—and therefore almost impossible to find with ground instruments. EPA also looked for particulate matter of 2.5 microns and higher—but these sizes are larger than the vaporized emissions.

After the BESS’s metals and chemicals exploded into skies above the facility and vaporized, the mist that formed traveled sideways, cooled off and descended onto surfaces of land and water—which NAML and Dr. Aiello sampled. (Thousands of residents in Monterey, Santa Cruz and San Bemnito Counties also inhaled this mist.)

WHO PROTECTS ECOSYSTEMS AND THE PUBLIC HEALTH?

Brian Roeder expected Vistra Corporation to protect its shareholders and deny responsibility for the fire and its health impacts. He did not expect the EPA’s inadequate testing or the state’s lack of support for the community or the fire’s victims. He salutes County Supervisor Glenn Church, who noted that “government does not have the knowledge to regulate this technology, and industry does not have the know-how to control it.” Supervisor Church aims to keep the facility off line until there is a full accounting of the fire’s cause and fallout.

While Roeder finds that a bill proposed by State Senator John Laird “lacks teeth,” he supports a bill introduced by State Assembly Member Dawn Addis. This bill would require local input in the permitting process and new regulations for new energy storage facilities.

Six months after the BESS fire ignited in Moss Landing, cleanup has yet to begin.

“If the EPA and local agencies don’t protect people or our environment,” Roeder asks, “then who will?”

These containers hold lithium-ion batteries. The ones at Moss Landing’s BESS were within a building.

WEIGHING BENEFITS V. RISKS

While states and countries rush to decarbonize, the very profitable BESS industry thrives with almost no regulations. Australians call BESS “the new gold rush.”

Brian Roeder believes in reducing our dependence on fossil fuels—safely. Safer energy storage means transparent supply chains, environmental and safety controls during manufacturing and end-of-life disposal. Safer battery storage technologies probably generate less profits than lithium-ion batteries. Roeder points to vanadium flow, aqueous zinc and sodium-ion batteries. While they’re less energy dense than lithium ion batteries, they’re more stable and present a lower and even non-existant risk of thermal runaway. Because they’re less energy dense, many of these new batteries require more land than lithium-ion storage.

The U.S. currently has 774 utility-scale BESS facilities. While developers plan to grow that number substantially, several communities have resisted and even banned them.

AFTER THE FIRE

NAML members have spoken with other people impacted by industrial disasters—like the chemical spill in East Palestine, Ohio; the lead pipes in Flint, Michigan; the open burn of batteries in Piqua, Ohio. Uniformly, corporate and government tell people that there’s nothing to worry about.

Brian Roeder observes that “with our culture’s pressure to keep moving forward, there’s no solution for industrial disasters. Officials simply don’t know what to do—so they say that nothing harmful has happened.”

Still, we need government agencies that protect our health, safety and welfare—and, for example, require warning consumers if fruit, vegetables topsoil and waterways are contaminated.

Two weeks after the Moss Landing fire, in late January, the Roeders abandoned their home. They rented AirB&Bs for several months, then bought a small house near the ocean, where clearer air helps Angie recover her health. Many neighbors—retirees and vets on fixed incomes—could not move and are still sick.

Along with other NAML members, the Roeders are in a lawsuit alleging that Vistra, battery manufacturer LG Energy Solution and utility provider PG&E bear responsibility for the disaster. The lawsuit asks that defendants be permanently barred from using nickel-manganese-cobalt batteries at the Moss Landing facility, that they be required to remediate the environmental contamination, and that plaintiffs exposed to the contamination be compensated for the costs of lifetime medical monitoring.

Dr. Aeillo warns that “we must understand the Moss Landing fire’s ecological impacts in the event that accidents like this happen again.”

SANTA FE COUNTY, NEW MEXICO

In Santa Fe County, New Mexico, AES Corporation proposes building a nearly 680 acre facility with 96 MW of solar power and 48 MW of four-hour duration lithium-ion BESS near Rancho Viejo and Eldorado.

Santa Fe County does not have staff trained to deal with a solar/BESS facility fire or its toxins. It has no emergency evacuation plan. Further, AES has only designed 30% of this project. If Santa Fe County Commissioners approve of it, the public will not have input on the design’s remaining 70%. Only the county’s fire marshal would review the remainder of the design—and approve it or not.

Santa Fe County Commissioners will meet Monday, August 11 and Tuesday, August 12 at the Commission’s Chambers on Grant Avenue to conduct a quasi-judicial public hearing on AES’ Rancho Viejo Solar LLC CUP application. The public is encouraged to attend.

EVENT WITH BRIAN ROEDER in SANTA FE

Brian Roeder (in person) and Jeanne Marie Colby, a Morro Bay attorney (joining by Zoom) who led her community’s successful effort to prevent a proposed BESS facility, will speak in the Jemez Room at the Santa Fe Community College Monday, July 28th, at 6:30 pm. New Mexicans for Responsible Renewables will host this free event.

RELATED BOOKS, FILMS and STUDIES

Bugryniec, Peter J., Erik Resendiz, et al, “Review of gas emissions from lithium-ion battery thermal runaway failure—Considering toxic and flammable compounds,” Journal of Energy Storage, 87 (2024).

Gibbs, Jeff, Director, and Michael Moore, Producer, Planet of the Humans, 2020.

Jensen, Derrick, Lierre Keith and Max Wilbert, Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What We Can Do About It, Monkfish, 2021. Documentary by Julia Barnes.

Troszak, Thomas, Why do we burn coal and trees to make solar panels? 2019.

Battery racks at Moss Landing before the fire.

Cleanview’s map of the U.S.’s 744 utility-scale battery storage projects.

https://neveragainmosslanding.org/

KATIE SINGER’s RELATED SUBSTACKS

Discovering Power’s Traps: a primer for electricity users May, 2024.

When Land I Love Holds Lithium: Max Wilbert on Thacker Pass, Nevada, June 2023. Like BESS facilities, e-vehicles depend on lithium. Why do environmentalists oppose mining it?

21 questions for solar PV explorers September, 2024.

Call Me a NIMBY Nov., 2023.

Who decides what’s sustainable? July, 2024. (Includes resources about unsustainability of solar PVs, wind turbines, A.I., data centers, smartphones and nuclear power.)