The dramatic events of the last 24 hours—the seizure of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro by US forces and his extraction to the United States—mark not just a geopolitical inflection point but a violent restoration of a racial and social hierarchy that has defined Latin America for five centuries. While Western capitals and media celebrate a “triumph for democracy,” the view from the barrios of Caracas is radically different.

To understand why Maduro retained the loyalty of millions despite economic collapse, and why his removal is mourned by the marginalized while elites celebrate, one must look beyond the simplified narrative of “dictator vs. democrats.” This is the story of a 500-year struggle between the mantuanos (the white elite) and the pardos (the mixed-race majority), a struggle in which the United States has just decisively intervened on the side of the former.

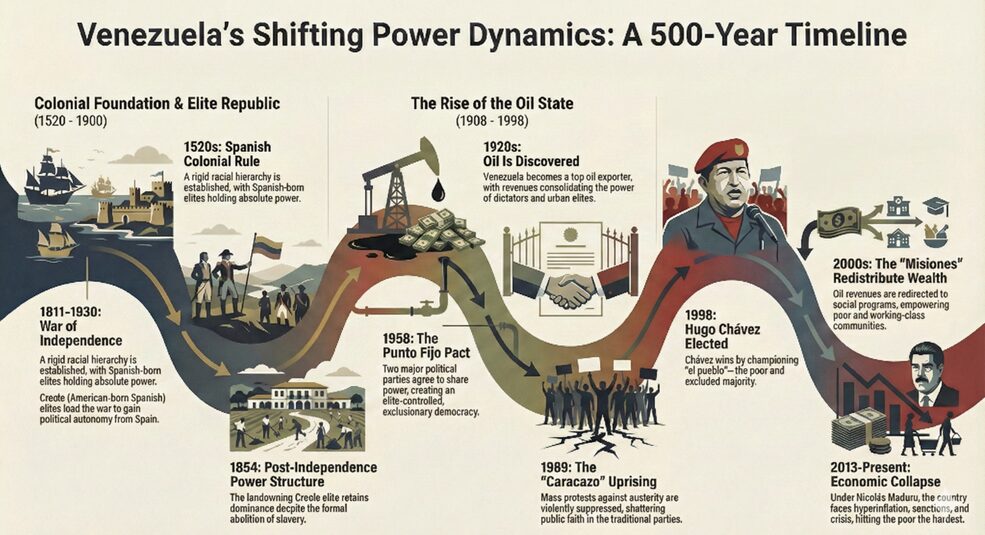

Understanding Venezuela’s History

To grasp the visceral nature of the Chavista movement, one must dig into the colonial bedrock of Venezuelan society. Since the Spanish conquest in the early 16th century, power in Venezuela has been color-coded. The colonial structure was rigid: Peninsulares (Spanish-born elites) held the highest offices, while Criollos (American-born Spaniards) owned the land and the enslaved. Beneath them lay the vast majority: the Pardos (mixed-race), enslaved Africans, and indigenous peoples, who formed the working class yet were systematically excluded from power.

The tragedy of Venezuelan history is that independence did not break these chains; it merely rebranded them. The War of Independence, led by the criollo elite Simón Bolívar, was fought largely by pardos who were promised emancipation. Yet, once the Spanish were gone, the criollo landowning elite retained their dominance. For nearly two centuries, despite formal legal equality, social and political power remained firmly in the hands of white and mestizo elites, while Afro-Venezuelans and indigenous communities remained politically disenfranchised.

This exclusion was formalized in the modern era through the “Punto Fijo Pact” of 1958. Often lauded in the West as a model of democratic stability, this agreement between the major parties was, in reality, a cartel of elites that ensured power circulated only within approved, white-mestizo circles. While the middle class expanded, the rural poor and Afro-Venezuelans remained excluded from the benefits of the nation’s exploding oil wealth. The “democracy” that the US claims to be restoring is, to many Venezuelans, simply a return to this pact of exclusion.

Chavismo as Identity Politics

The rise of Hugo Chávez in 1998 was a psychological earthquake because it shattered this colonial continuity. Chávez, a man of mixed indigenous and African descent (pardo) from a poor background, did not just win an election; he inverted the country’s historical pyramid. For the first time, the face of the state mirrored the face of the majority—the “pueblo”.

The Chavista movement represented a profound assertion of identity. It challenged the “myth of racial democracy” that Venezuela had long promoted, openly addressing structural racism and elevating Afro-Venezuelan and indigenous symbols. Under the 1999 Constitution, the country was renamed the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, and the state explicitly recognized the rights and heritage of indigenous peoples.

Maduro, a former bus driver, inherited this mantle. His government continued to prioritize the elevation of non-white citizens into the military command, judiciary, and cabinet—spaces previously reserved for the upper classes. The visceral hatred directed at Maduro by the traditional opposition is often coded with classist and racist undertones. To his supporters, his “kidnapping” is not a legal arrest but a vengeful counter-revolution by the descendants of the Criollos, who have always viewed governance by a “bus driver” as an aberration of the natural order.

What Chavismo gave the people

Critics point to the economic ruin of Venezuela as proof of socialism’s failure. However, a well-researched view requires acknowledging the massive, tangible gains made under Chavismo before the stranglehold of sanctions and mismanagement took hold.

In the early years of the Bolivarian Revolution, the state redirected oil revenues away from elite enrichment and into “Misiones”—massive social programs focused on health, education, and housing.

- Health & Nutrition: The state bypassed traditional, exclusionary bureaucracies to bring healthcare directly to the shantytowns. The CLAP food distribution networks[1] became a lifeline for the poor, ensuring that the oil wealth finally reached the dinner tables of the working class.

- Education & Culture: Illiteracy was aggressively targeted, and higher education was opened to the poor. Culturally, the movement fostered a sense of pride in indigenous and African roots, challenging the Euro-centric cultural domination of the past.

- Political Inclusion: Through community councils, the poor gained a political voice and unprecedented access to state resources, fundamentally altering the class structure.

The economic collapse cannot be divorced from the context of the 1980s and 90s, where neoliberal reforms and austerity led to the Caracazo of 1989—a mass protest by the poor that was violently suppressed by the old regime, leaving hundreds dead. The memory of that massacre drives the loyalty to Maduro; his supporters know that the “old elite” now celebrating his removal are the same political lineage that ordered the shooting of the poor in 1989.

The Nobel Prize: The West’s Seal of Approval

Nothing illustrates the West’s true intentions more clearly than the awarding of the 2025 Nobel Peace Prize to opposition leader María Corina Machado. While the committee in Oslo lauded her “tireless work promoting democratic rights”, a closer look at her biography and policy platform reveals exactly why she is the preferred candidate of the Global North. Machado is not a woman of the people; she is the daughter of a wealthy steel baron, educated at elite private institutions like the Andrés Bello Catholic University, and grew up with advantages that most Venezuelans could only dream of. She is the living embodiment of the sifrino class—the light-skinned, Euro-centric elite that Chavismo sought to displace.

Her Nobel Prize was less a recognition of peace and more a geopolitical signal: a “green light” for the restoration of a business-friendly regime. Machado has been explicit about her economic plans, advocating for a massive and transparent privatization process of state assets. Most critically, she has called for the privatization of PDVSA, the state oil company, aiming to turn Venezuela into an “energy hub” that welcomes foreign capital with open arms. To the Western powers, her “peace” means the pacification of the working class and the reopening of Venezuela’s vast oil reserves to ExxonMobil and Chevron. By crowning her with a Nobel, the West has sanctified the return of the mantuanos, signaling that the only “democracy” it respects is one willing to sell its national resources to the highest bidder.

Latin America’s History of Disruption

This racial dynamic is the central conflict of modern Latin American history. The last century has witnessed a slow, painful struggle to wrestle control from Euro-centric oligarchies. We saw this in Bolivia with Evo Morales, and in Peru with Pedro Castillo—leaders who, like Chávez and Maduro, represented the indigenous and rural hinterlands against the white-mestizo urban centres.

The US intervention is perceived in the region not as a defence of human rights, but as a “neo-colonial policing action.” It sends a chilling message: while mestizo and indigenous populations may vote, they are not allowed to rule if their policies threaten the strategic interests of the North or the comfort of the local mantuanos. The removal of Maduro is the removal of an obstacle to the re-establishment of the dominance of the white/mestizo elite.

An Analogy for India: The Caste Lens

For an Indian observer, the events in Venezuela are best understood not through the lens of “Democracy vs. Dictatorship,” but through the lens of caste.

Imagine an India where, for centuries, the Prime Minister, the Cabinet, and the Supreme Court were exclusively Upper Caste. They controlled the economy and the narrative, while the Bahujan majority (Dalits, OBCs, and Adivasis) were the labour force, visible only as servants.

Then, a leader emerges from a Bahujan background—a former sanitation worker or bus driver. He radically restructures the state, taxing the Upper Castes to fund health and education for the Lower Castes. He empowers OBC generals and Dalit judges. The Upper Castes are horrified; they call him uneducated and a tyrant.

If foreign forces were to then kidnap this Dalit Prime Minister and install a leader acceptable to the old Upper Caste elite, the “Upper Caste” sections might celebrate the “return of merit.” But the Bahujan majority would see it as a violent re-imposition of Manu’s hierarchy. This is what is being attempted in Venezuela.

Removing the “Bus Driver” and putting the Peninsulares back in charge will not be easy though, even with all the money and might of US imperialism. As both the country’s elite and US warmongers are likely to find out, the ordinary folk of Venezuela will defend till death what they have acquired through the Bolivarian Revolution of Hugo Chavez.

And for them, this is not just about power and access to resources, but respect and dignity denied to them for centuries.

[1] Comité Local de Abastecimiento y Producción, or Local Committees for Supply and Production is a Venezuelan government-run program that distributes subsidized food boxes or bags directly to households in response to severe food shortages.