Topic: Less of What We Don’t Need

-

Cobalt Red, How The Blood Of The Congo Powers Our Lives

—

by

“Unspeakable riches have brought the people of the Congo little other than unspeakable pain.” So writes Siddharth Kara in Cobalt Red, How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives . Kara surrounds his subject—artisanal cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo—with broad historical and economic context. He explains battery technology and the…

-

Tribes Say SunZia Line Threatens San Pedro River, Sue To Stop Work

—

by

Two Arizona tribes filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Department of the Interior and the Bureau of Land Management for approving a high-voltage transmission line, alleging the government failed to account for historic and cultural sites through the line’s San Pedro Valley route. Fifty miles of the transmission line will traverse the middle and lower…

-

Planning For Degrowth

—

by

There was an article in Nature from late 2022 on degrowth that got some sudden attention over the holidays because economists and tech bros noticed it and turned out on social media to do some hating. In fact the lead author, Jason Hickel, claimed on Ex-Twitter that as a result the paper was the most-read on Nature during the break. …

-

Gaza Horrors: 1000 Amputations with No Anesthesia

—

by

Over 1000 children in Gaza have had their limbs amputated without anaesthesia. It’s a doctor’s nightmare with little medical supplies. The number has just been released by UNICEF, the UN children’s agency and points to the devastating situation of children in Gaza. A doctor amputated his son’s limb without anaesthesia. The pain was so sever…

-

The Final Nail In Psychiatry’s Antidepressant Coffin

—

by

Historically, there have always been some patients who report that any treatment for depression—including bloodletting—has worked for them, but science demands that for a treatment to be deemed truly effective, it must work better than a placebo or the passage of time without any treatment. This is especially important for antidepressant drugs because all of…

-

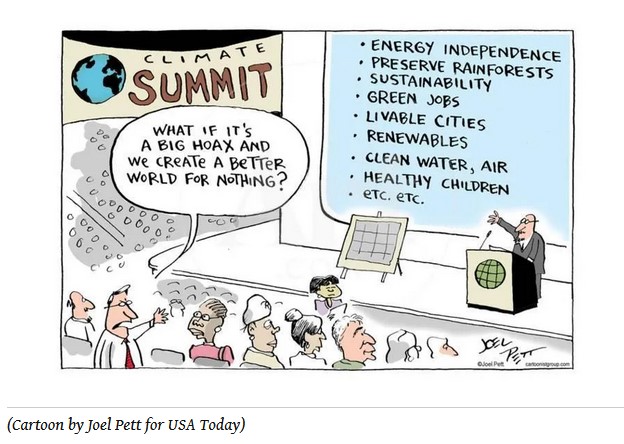

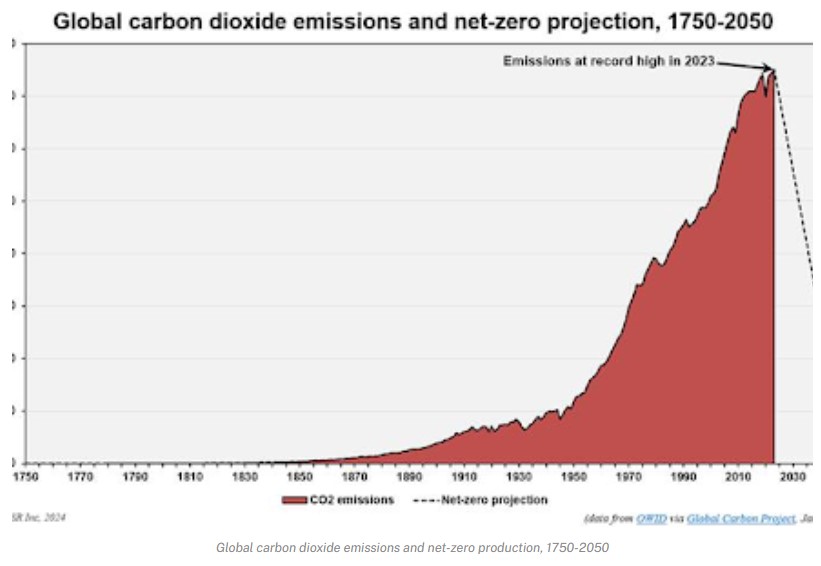

Climate Change and Energy Transition: The 2023 Scorecard

—

by

Confusion sometimes results from failure to distinguish production capacity from actual generation since solar and wind installations typically generate only 20 to 50 percent of their theoretical capacity. To reach net zero emissions by 2050 by providing 100 percent of total global energy from renewables, we would need a nearly ten-fold increase in renewable energy…

-

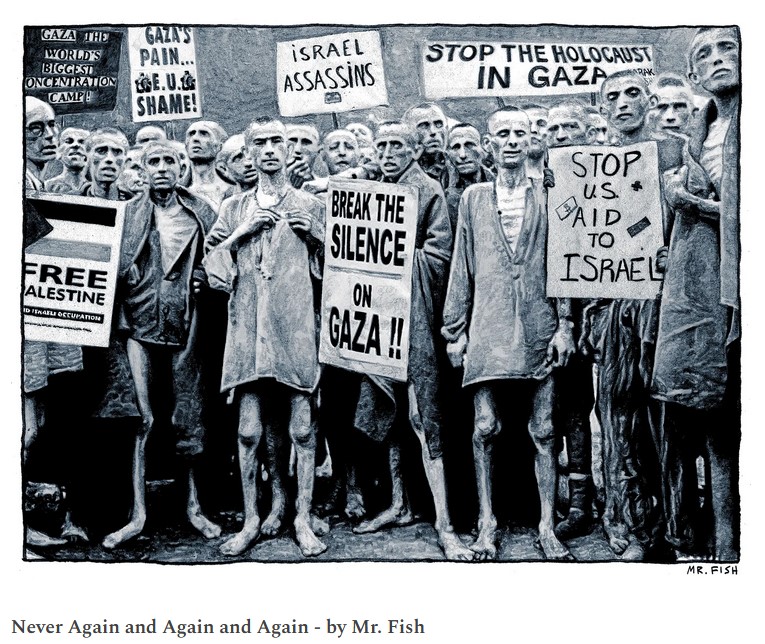

Israel’s Genocide Betrays the Holocaust

—

by

Israel’s lebensraum master plan for Gaza, borrowed from the Nazi’s depopulation of Jewish ghettos, is clear. Destroy infrastrutrue, medical facilities and sanitation, including access to clean water. Block shipments of food and fuel. Unleash indiscriminate industrial violence to kill and wound hundreds a day. Let starvation — the U.N. estimates that more than half a million people are already starving…

-

What Abandoning Fossil Fuels Could Look Like In The Arab World

—

by

For the second year in a row, world leaders met in the Arab world to negotiate the future of the planet. As a backdrop to the United Nations climate conference in Dubai, it’s a fitting venue for a planet-wide shift that scientists say needs to happen: The region has extensive deposits of oil and gas,…

-

The Green New Deal Is the Opiate of the Masses

—

by

What kinds of measures are you taking, personally, to prevent global warming? Do you carry a thermos so you don’t end up buying drinks in plastic bottles? Did you buy an electric car? These good deeds are meaningless. They can even cause more harm than good. Simply thinking that such actions are effective countermeasures can…

-

Israel, Gaza, and the Struggle for Oil

—

by

Why would Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the Biden administration risk their standing in the world and ignore calls for a ceasefire? Did they have an unspoken agenda? As a chronicler of the endless post-9/11 wars in the Middle East, I concluded that the end game was likely connected to oil and natural gas,…